Over the last 10 years, the average weight of vehicles sold has increased by about 9% or around 100 kgs. Sales of small SUVs have increased 5 times, becoming the most sold vehicles in 2022 with about 4 million new units put on roads across Europe. Large SUV sales have also further increased by 7 times, although the total sales volume is roughly 700,000 units.

Considering the impact of weight on consumption and on greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) and primary energy demand (PED) for production, a compact family car – with a 100 kg average increase in weight – is responsible for about 1.4 tonnes of additional greenhouse gas emissions and 5.7 MWh of extra energy used.

According to the European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association (ACEA), 9.3 million vehicles were sold in 2022, of which 12.2% were battery electric vehicles (BEVs). This leads to a revealing calculation – assuming 8 million vehicles are, on average, 100 kgs heavier, the impact of this weight increase on the climate is the equivalent of about 200,000 extra vehicles on European roads.

The impact of added weight is one of the findings of Green NCAP’s latest Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of GHG and PED of vehicles in 2022. Green NCAP is a green vehicle assessment programme hosted and supported by the New Car Assessment Program in cooperation with European Governments. The organisation has test laboratories in 8 European countries and aims to increase awareness of the environmental impact of the vehicles.

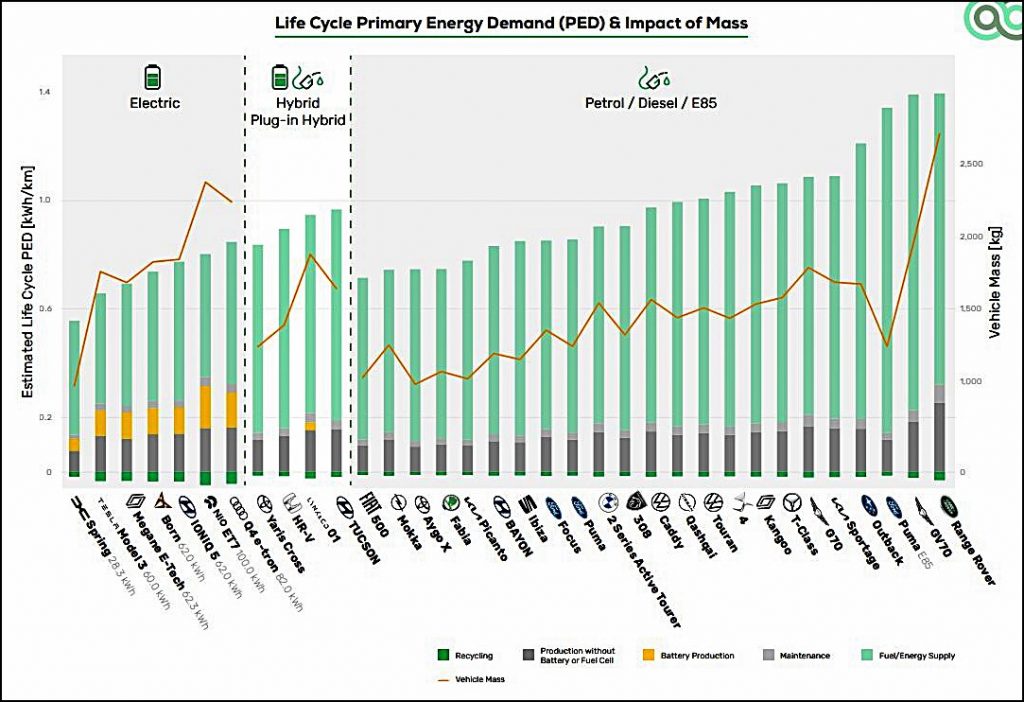

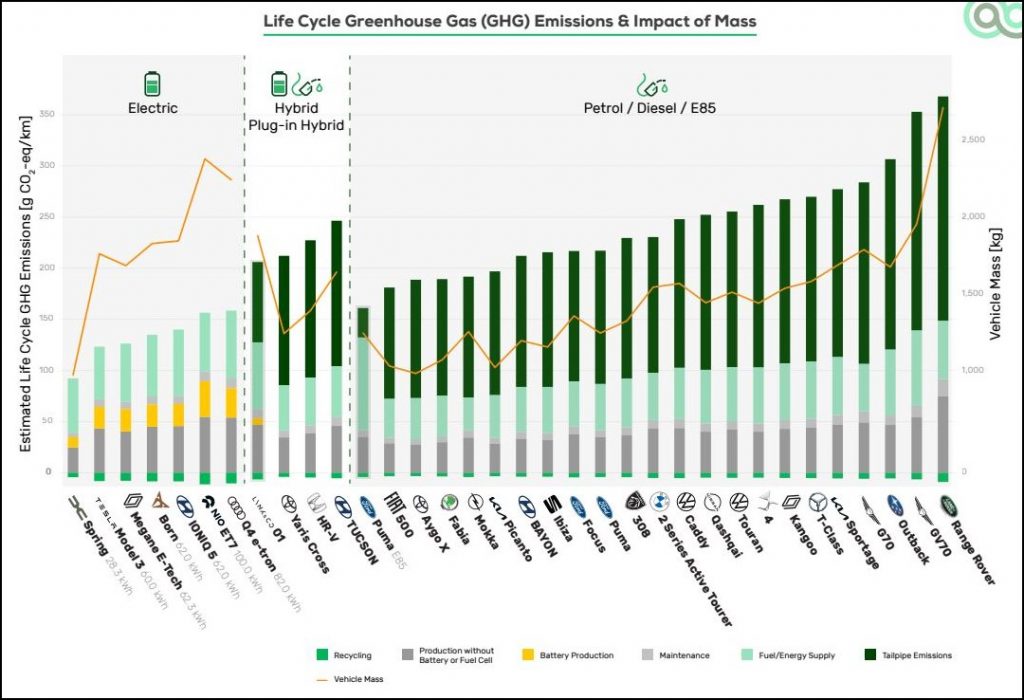

Green NCAP tested 34 passenger vehicles with different powertrain types: battery electric, hybrid electric, conventional petrol and diesel, and one vehicle, the Ford Puma, that runs on alternative fuel. The calculations used the interactive LCA tool that is available for consumers on Green NCAP’s website. The calculations are made based on the average energy mix of the 27 EU Member States and the UK, and an average mileage of 240,000 kms over 16 years.

Green NCAP’s results show that the current and continuous trend towards larger and heavier cars, significantly increases the negative impact on climate and energy demand. This drives not only a rise in fuel and electric energy consumption, but also creates a wider footprint in vehicle and battery production. Consumers and manufacturers also share the burden for this trend given their steady interest in larger cars, in particular SUVs.

LCA results from the 34 vehicles showed that BEVs are ahead in reducing greenhouse gases with 40 ‑ 50% less emissions compared to conventional petrol cars, depending on the model chosen. In terms of primary energy demand, the differences between electric and conventional cars are less.

The hybrid electric SUVs that were tested had higher fuel consumption and due to increased emissions in the usage phase, their life cycle values were in the range of 200 ‑240 g CO-equivalent/km and an estimated 0.85 ‑ 1.0 kWh/km. These numbers lie between the values of a large electric SUV and a conventional petrol or diesel-powered counterpart.

Noteworthy are the results of the bio-ethanol (E85) operated Ford Puma, as compared to the same car in petrol model. This model has greenhouse gas emissions reduced to a level closer to the range of BEVs. In this case, the processes needed for the bio-fuel production increase the Puma’s life cycle energy demand by 57%, yet given 60% of the total energy needed is renewable, much less fossil fuel is used.

These calculations show the considerable differences between each vehicle’s impact on the environment, but they also reveal the significant influence of mass on GHG and PED. This is clearly seen for all powertrain types even though the correlation might be slightly distorted for some models due to differences in aerodynamic drag or powertrain efficiency.

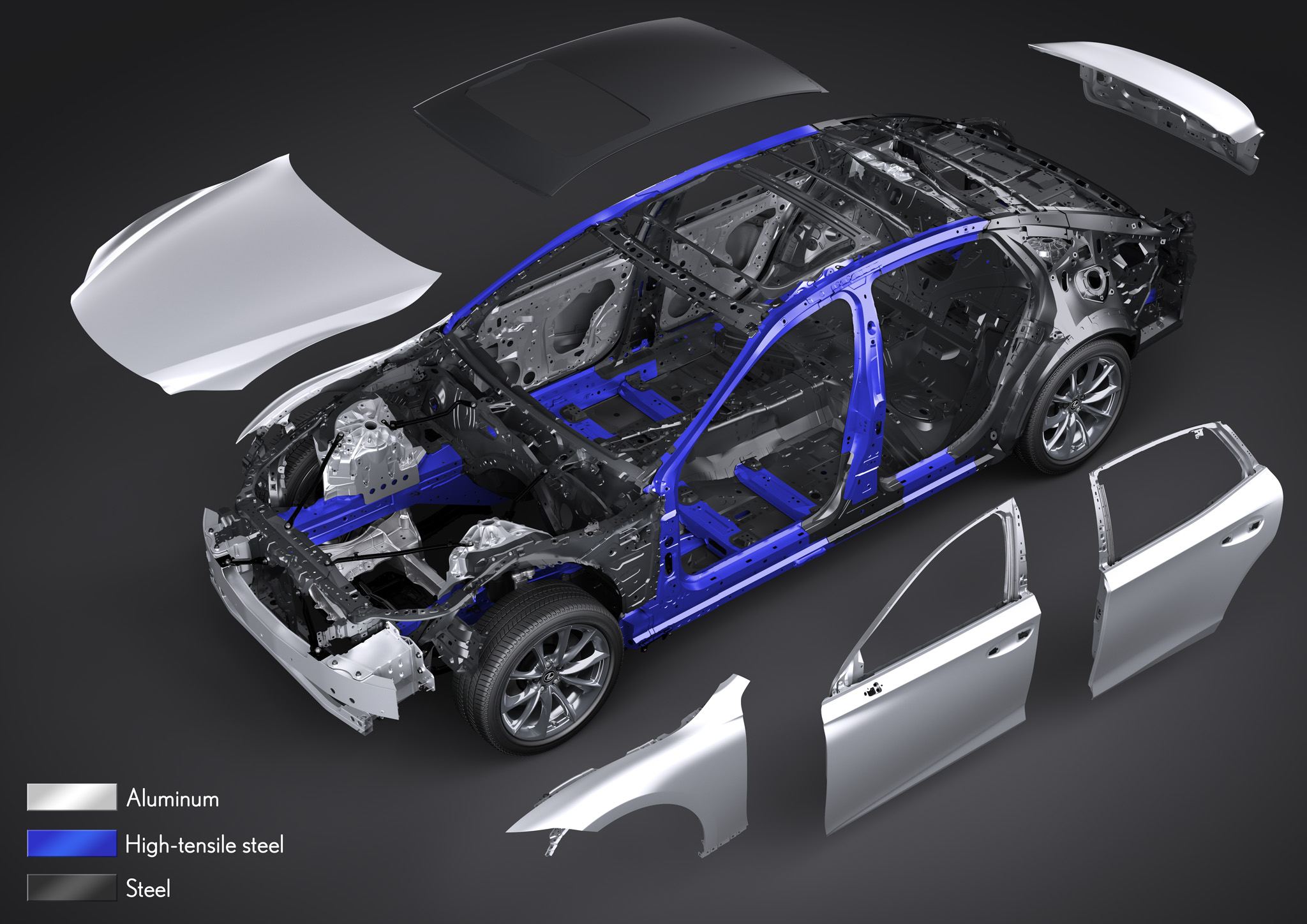

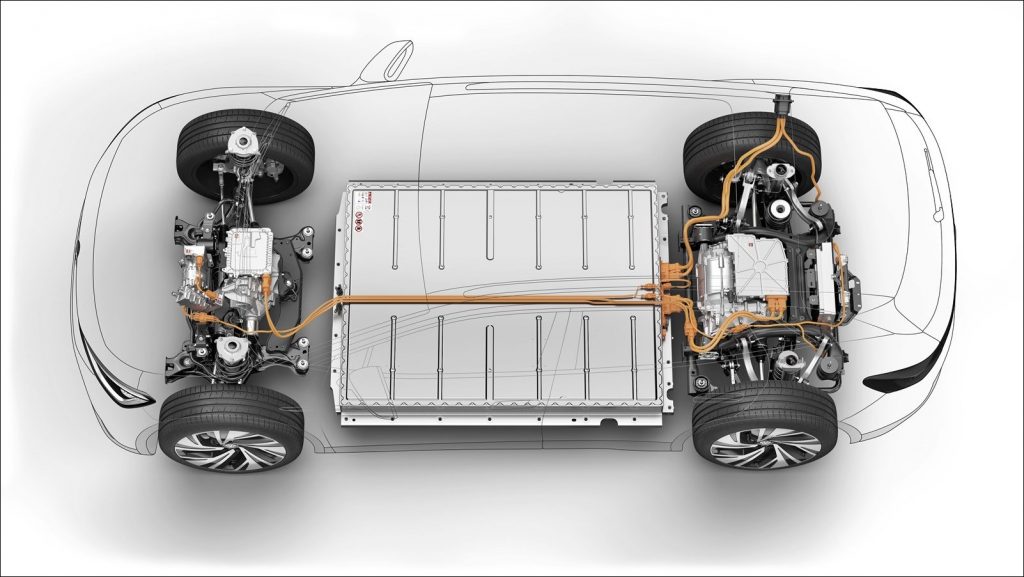

Nevertheless, the overlying message is clear: the heavier the vehicle, the more harm it does to the environment and extra energy is required to propel it. In general, BEVs emit significantly less greenhouse gases over their lifetime but some of the gains are lost due to their increased weight. Though the drivetrains may have less weight, the battery pack imposes a substantial weight.

“Electric vehicles and electrification in general offer huge potential in reducing greenhouse gases but the ever-increasing trend of heavier vehicles diminishes this prospect. To counteract this, Green NCAP calls on manufacturers to reduce the mass of their products and calls on consumers to make purchasing decisions that not only consider the powertrain of their new cars but also consider their weight,” said Aleksandar Damyanov, Green NCAP’s Technical Manager.