Two years ago, at the Third Global Ministerial Conference on Road Safety held in Stockholm, Sweden, participants from 140 countries (including Malaysia) agreed to no less than 18 resolutions linking road safety to sustainable development with a key aim of halving the number of traffic deaths by 2030.

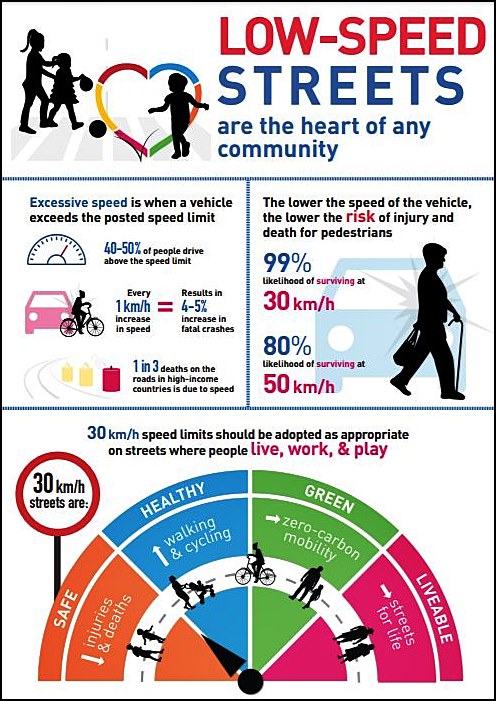

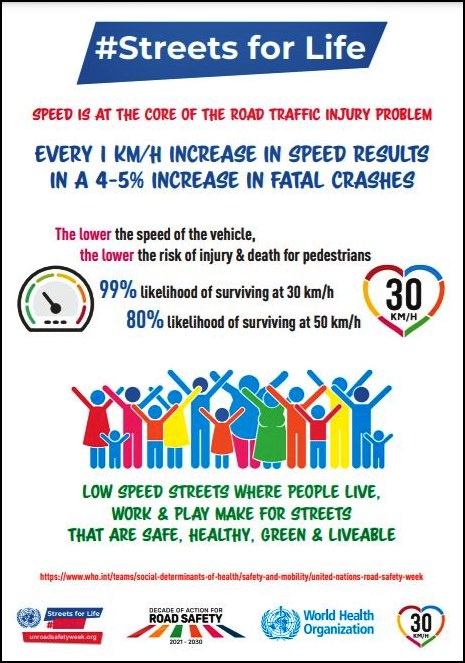

The ‘Stockholm Declaration’, as it came to be known, reflects the resolve of UN members to apply speed management as a key road safety intervention. The main element of this is to strengthen law enforcement to prevent speeding and set a maximum road travel speed of 30 km/h as appropriate in areas where vulnerable road users (pedestrians, cyclists) and motorized vehicles mix.

30 km/h, a lower speed than the typical 50 km/h that has been applied, has been chosen based on studies from recent decades in cities such as Graz (Austria), London (Great Britain), New York (USA) and Toronto (Canada) which indicated that limits set at that speed in certain zones has reductions – often significant – in road traffic crashes, injuries and deaths. Evidence shows that 30 km/h streets where people mix with traffic not only save lives, but also promote walking, cycling and a move towards zero-carbon mobility. Today, more cities around the world have established 30 km/h zones and many lives have been saved.

“Many decades ago, the world was at a crossroads: a transport system centered around the private motor vehicle versus one which maintained a share of the road for pedestrians, cyclists and users of public transport. We are again at a crossroads. I call on all policy-makers to work with national and local authorities to reduce urban speed limits to 30 km/h, as a step towards giving streets back to people and ensuring those streets are protective of health and the environment. Low-speed streets – the heart of every community – are streets for life,” said Etienne Krug, Director, Department of Social Determinants of Health at the World Health Organization.

In Malaysia, perhaps due to the disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the introduction of 30 km/h zones had not gained a lot of attention earlier although MIROS had said it was preparing a proposal for the relevant authorities last May. It gained more attention this month when the Transport Minister mentioned it and said that his ministry would discuss the speed limit with various stakeholders.

As in other countries where the lower limit has been introduced, there will be some who are not agreeable to the idea although if it will save lives, why not? According to the minister, excessive speed is not the only factor that causes accidents and this is where MIROS (Malaysian Institute of Road Safety), which has volumes of data, has made a case for 30 km/h.

The proposed speed limit is not a ‘blanket’ speed limit and will be applied in areas that are identified as having a lot of mixing between pedestrians, cyclists and motor vehicles. The highways would not be subject to such a limit for obvious reasons but in residential areas and city centres, it would make a lot of sense to have motor vehicles travel slowly.

There are however some arguments where a lower speed can be counter-productive in other respects. Congestion might occur and in Singapore, speed limits were raised on a few roads because they found that the flow could be more efficient if the vehicles travelled 10 km/h faster. In Malaysia, though, our city roads are so congested that there is a ‘natural’ speed limit already working and it doesn’t even need enforcement!

There is also another danger in making motorists drive too slowly and that is a possible reduction in concentration. As their speed drops, they may feel that it is so slow that they can’t get into trouble and start to look around – and miss seeing a pedestrian crossing the road. Higher speeds usually make people give more attention to their driving as they realize that one mistake and they could go off the road. But as with many things, humans can also adapt and in time, a later generation of motorists will come to be used to lower speeds.

Motorists should also not forget that a 30 km/h speed limit is also for them and not just for ‘others’. There will be occasions when they too walk along roads, whether in their own neighbourhood with their children or in the city on the way to a meeting after parking. They may also have family members who walk more than use a car, so their safety should also be considered.

In a perfect world, we would not need speed limits because everyone would be sensible enough to drive at a speed that is safe for themselves and when there are pedestrians, safe for those other road-users. We wouldn’t have many accidents – and we should have even less with all the advanced safety systems today. Unfortunately, there are too many motorists who do not use common sense and who are irresponsible, so speed limits have been necessary, backed by laws that punish those who break them.

DENSO’s Third Generation Global Safety Package offers increased active safety