‘300 SL’ was the designation of the competition car from Mercedes-Benz with which the brand returned to international motorsports in 1952 for the first time after the Second World War. Although this car was not sold to the public, it did light the fuse for the development of the later SL-Class.

The development of the 300 SL began in 1950, when Mercedes-Benz began to think about a return to racing. The attempt to reactivate the 1939 W 154 Grand Prix racing car, however, met with failure in Argentina in 1951. So the engineers pressed forward the development of the new racing car, some of the components of which came from the 300 model.

SL means ‘Super Light’

In June 1951, the Board decided to resume participation in racing events from 1952 and gave approval for the construction of the 300 SL, the two letters meaning ‘Super-Light’. Its M 194 engine was derived from the 300 type unit, the M 186, with an overhead camshaft, large inlet valves, combustion chamber in engine block and pistons, a displacement of 3 litres and an output of 115 bhp. For racing, the engineers increased the engine’s output to around 170 bhp.

The sports engine differed from the one installed in the saloon and coupe not only in its output, but also in its installation position, slanted 50 degrees to the left, and in having a dry-sump lubrication system, which due to the omission of the oil sump, enabled a lower installation height.

Weight savings were hardly possible with the engine and the transmission of the W 194 that was in the process of being created. And this was also true of the heavy steel axles which had also been taken from the 300 model. That left only the frame and the exterior skin for any possible weight-savings.

Early use of the spaceframe

Another possibility for enhancing competitiveness was to create a body as aerodynamic as possible. This led to a previous idea of a lightweight tubular frame and the designers then carried the concept forward to its logical conclusion – a lightweight, extremely torsionally-rigid frame. This consisted of very thin tubes joined together to form triangles, whose tubular elements were only subjected to tensional and compressive forces.

The entire frame weighed just 50 kgs and became the backbone of the W 194, as well as the basis for the production version of the 300 SL (W 198 I) and for the successful 1954/55 racing and motorsports car.

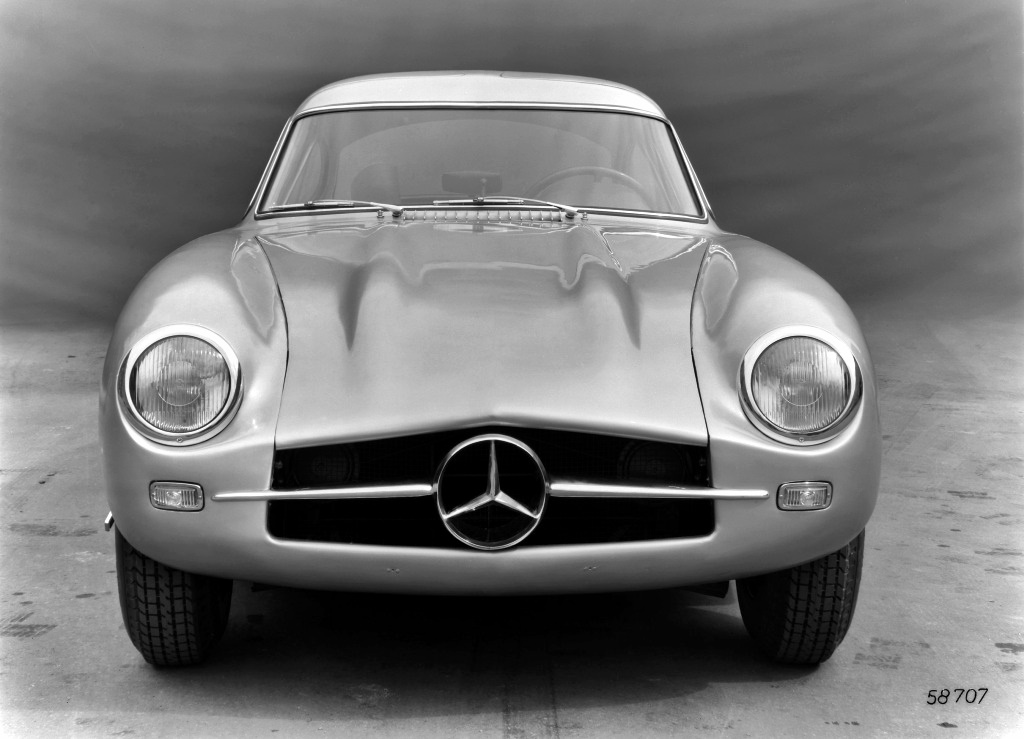

No effort was spared with the aluminium body. Thanks to the canted position of the engine and the aerodynamic profile, the car was very low, free of trim right down to the underbody, with an elegant low bonnet line, intuitively round-shaped, with recessed headlamps and its wheels entirely covered by the bodywork.

The classic Mercedes-Benz radiator shape was replaced by a flat racing car front end analogous to that of pre-war cars. The Mercedes star dominated the radiator grille prominently. The coupe greenhouse was made as narrow as possible, with a strongly raked windscreen, curving towards the A-pillars. The large rear window flowed over into the aerodynamic rear end.

The result was a relatively small frontal area: 1.8 square metres. A drag coefficient was measured on a 1:5 scale model and found to generate a Cd value of 0.25. That was even without taking into account the realistic airflow through the engine compartment.

Origin of the ‘gullwing’ term

In order to lend a spaceframe the desired high rigidity, it has to be as wide as possible in the passenger cell sector. This requirement led to the spectacular and later so famous gullwing doors. In the first cars, the door opening began at the waistline. The doors, deeply cutting into the roof, opened upwards, creating an image reminiscent of outspread wings. This is how the term ‘gullwing’ originated (created by the North Americans).

In order to facilitate access over the high side sill, the bodywork designers had even originally intended to have an access step in the lower part of the vehicle body flank; however, this feature was never realised. Although the FIA regulations of the time did not specify the type and direction of opening doors, the stewards were still somewhat disagreeable when the car was presented to them for scrutineering before the Mille Miglia in May 1952. To avoid any future protests, after the race in Italy, the doors were extended down into the car’s sides, thereby assuming their final shape.

The interior was fully padded and lined, radiating a level of comfort unusual for racing cars. Speedometer and tachometer were accommodated under a common hood, and below that were the gauges for water temperature, fuel pressure, oil temperature and oil pressure. Even a stopwatch was installed. The bucket-type seats with high side sections were covered with tartan-style woollen fabric; the four-spoke steering wheel was removable to facilitate climbing in.

Ten W 194 cars were built for the 1952 season. After the Le Mans race, it was planned to enter the SL in a sportscar race on the Nurburgring. To shed as much weight from the competing cars, the engineers cut the roofs off three coupes. A fourth car had been set up as a roadster right from the start. To permit easy access, the section of the door extending into the side of the car was retained, and a small windscreen was mounted to deflect air and flying insects. This resulted in a weight advantage of 100 kgs over the coupe.

Multiple racing victories

The year 1952 was an extremely successful one for Mercedes-Benz racing cars with victories in various races in Europe. The last big adventure of the season was participation in the third Carrera Panamericana Mexico, a 3,100-km race through Mexico. Mercedes-Benz entered two coupes and two roadsters, all powered by engines with 180 bhp. At the end of the 5 days and 8 long stages, the team collected a legendary double victory for Mercedes-Benz.

Mercedes-Benz Museum offers a new perspective with indoor drone tour (w/VIDEO)