Although I’ve reported on many cars having anniversaries during the 43 years I’ve been a motoring journalist, the 35th anniversary of the Proton Saga today is one that is special. As a Malaysian, the creation of the first National Car was a significant development in the industry that I have been covering. It took the auto industry to the next level and served as a catalyst towards industrialisation.

In the early 1980s, before Proton started, there were over 20 different brands in the market which had a Total Industry Volume of 50,000 to 60,000 units a year. It was therefore a fragmented market with each brand having small volumes, which didn’t make for efficiency nor economies of scale. A big manufacturer with larger volumes would have economies of scale which would keep production costs low – as Henry Ford had shown.

The bigger volumes would also make it viable for other upstream businesses to start, like parts suppliers. In fact, at that point in time, the auto industry was the largest type of integrated industry in the world with extensive upstream and downstream activities. Most people think only of cars being made but there are thousands of related industries – tyres, oil, electronics, petrol stations, workshops, etc. The auto industry was a major contributor to the economies of America, Germany and Japan because of this and it could also do the same for Malaysia’s economy.

And so a National Car project was started and while I understood the reasons for it, in the business that I was in, there was also some worry. Would the government close off the market and allow only Protons to be sold? If that happened, what new cars could our magazines write about? One joke was that perhaps we could test different versions of the Saga each month – one month, we might test a red Saga and see if it went faster and the following month, we would do a test with different wheels!

But as it turned out, the government didn’t close the market to other brands although it gave Proton special privileges like tax-exemption on parts which helped lower its production cost and gave it a significant price different from other models. This was important because the Saga was ‘a new kid in town’ and it would have been tough against the established models, the patriotism of Malaysians notwithstanding.

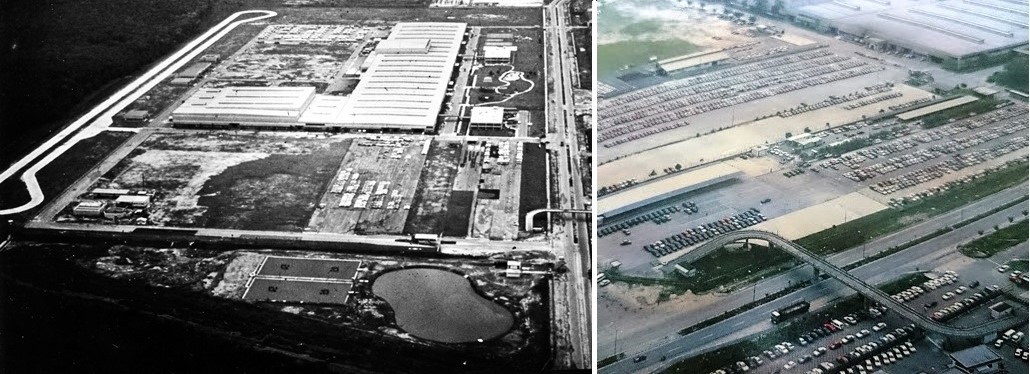

My coverage of Proton and the Saga began in 1983, two years before the car was launched. There were periodic briefings at the site where the factory was being built and I remember seeing big holes in the ground where the giant stamping machinery would be placed. The location was what was was then reharded as an ‘ulu area’ as it was in a newly cleared estate area that was to become an industrial park.

During the briefings, one of the questions I asked was about model changes. I wondered how long the model would be produced and whether there would be succeeding generations, like what other manufacturers did. Or would it be produced a long time like the Hindustan Ambassador which was still produced in its original form in India after having been launched in the 1960s. Or worse, like the VW Beetle which was unchanged from after World War II till 2003!

The General Manager who answered gave this answer: “Of course we will develop new models from time to time – you know, like Porsche – and also add more models. Just give us time.” Porsche…hmmm… okay….

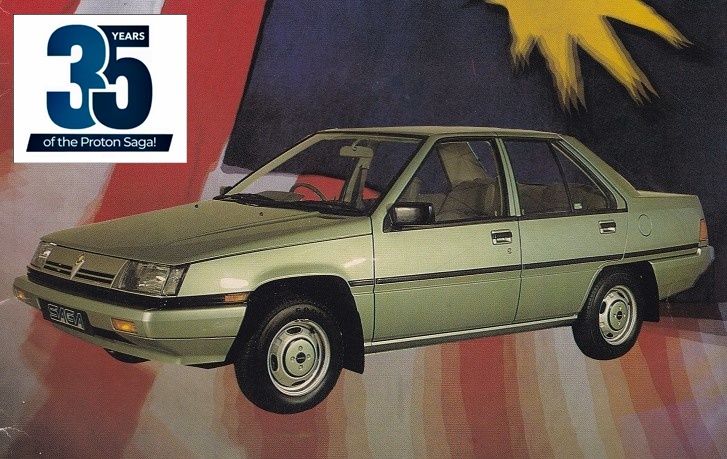

The project was Top Secret and when the first prototype was flown to Subang airport for Tun Mahathir to view, the hangar was surrounded by commandos. Back then, spyshots were unheard of and so the design of the Saga remained very much unknown till March 1985. That was when the first two official pictures were released and they were only of the exterior.

It didn’t have the ‘minangkabau roof’ that cartoonist Lat suggested, of course, and the design was familiar as it was adapted from a Mitsubishi model. Being new, adapting a model that was fully engineered was the fastest way for Proton to get going and I saw nothing wrong with it though some would say it was just a ‘badge engineered’ job. The industry was getting more competitive and Proton did not have the luxury of time to learn and develop in-house, as Toyota did in the 1930s. There was no time for trial-and-error and Proton had to get it right first time to convince at least Malaysians that it could make good cars.

An opportunity to drive the car before launch

Between March and July when the car was launched, there was increasing excitement and I looked forward to the launch. Much to my surprise, I got a call from EON (which was responsible for dealing with the media as it had a domestic marketing role) inviting me to their office which was opposite the factory. I was told that I would be provided with a car to test – and that was a few weeks before the launch! What a privilege as I would be among the first people not involved in the project to drive the car.

There were about a dozen of us motoring media (no bloggers then) from the magazines and newspapers and we had a briefing before we were handed the keys and off we went. Most of us chose the road to Puchong which was not the highway it is today. It was a winding road through estates and on one corner, one of the cars skidded and almost went off the road!

The problem we found was that the cars had too much air in the tyres, so it was not a design fault. What I suspected was that the excessively high pressures were because the car were rushed out of the factory for us and no one had thought of lowering the pressures to what was recommended. Often, tyres are pumped up harder because the cars may sit in the yard a while so it’s better to keep them hard so they do not deform.

The other thought was that someone felt that since we were going to test the cars, they needed higher pressures. This was what was done for cars that were racing on the track, so that was a possibility. Anyway, once we got the pressures corrected, the car’s handling was fine.

Super cold air-conditioning system!

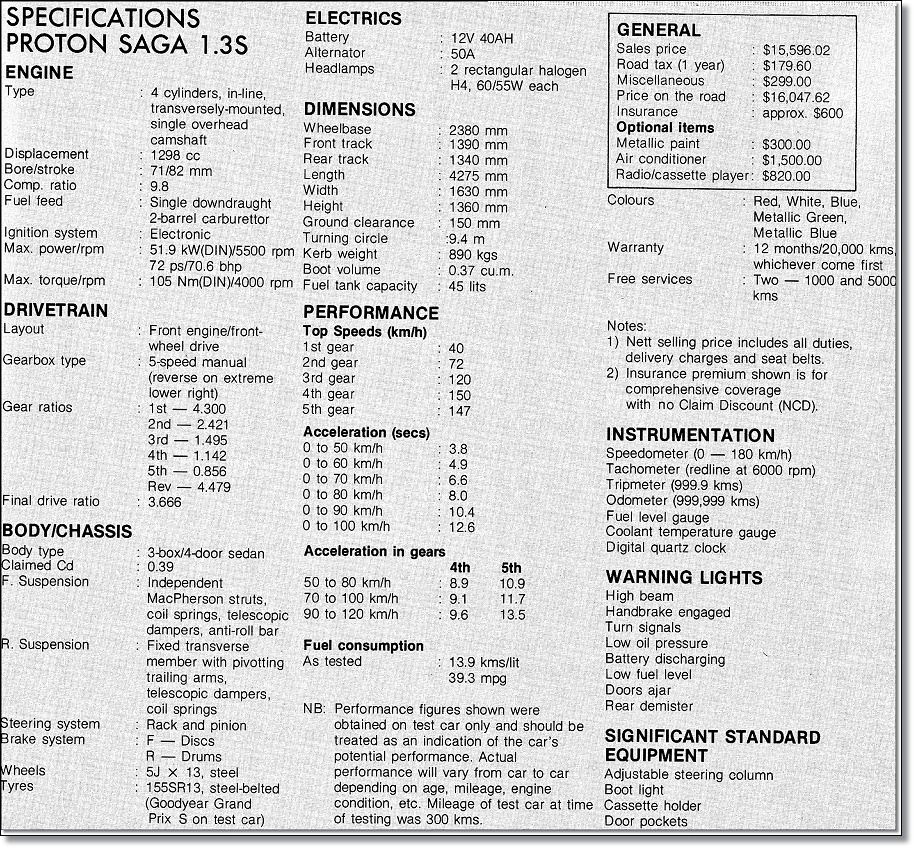

Generally, the Saga was like the Japanese cars of that period – it was, after all, an adaptation of a Mitsubishi Lancer. One thing that I remember being commented on was the air-conditioning system. The integrated type was slowly being introduced and the Saga had it but what impressed was its coldness! Clearly, the need for good cooling was a priority and Proton made sure it was suitably ‘Malaysianized’.

The first Saga came with steel bumpers at a time when the industry was transitioning to plastic bumpers (or a material known as polypropylene) to reduce weight. I didn’t have a critical view of steel bumpers though they were a bit heavier because I felt that they were easier and cheaper to repair and paint when damaged (just knock back and repaint). Proton gave that as one reason although it was also believed that the technology for plastic bumpers was expensive at that time and Proton couldn’t afford it. Those who had cars with plastic bumpers would also discover that if there was damage, replacement cost was very high.

How Malaysians ‘tested’ the Saga

The cars we drove were not camouflaged as, by then, the whole nation knew what the Saga looked like. In fact, EON even put stickers on the car which identified us and our publications. So wherever I went, people looked and pointed and stared at the car. And when I parked, a crowd would gather to get a closer look. As I thought of myself as an ‘ambassador’ for Proton, I did my best to answer questions and opened the bonnet many times to let people see the engine and let them get inside the cabin.

There was a lot of ‘Malaysian testing’ which involved the doors. They were opened and slammed shut so many times that I worried they would drop off! But the car was well engineered and survived the ‘punishment’, along with the tyres which were also kicked for reasons I don’t understand. There were probably tiny dents around the bodywork as people knocked on the panels, perhaps to check if the Saga was also a fragile ‘milo tin’ car, as the early Japanese cars were perceived.

On some occasions, I was followed as people wanted to look at the Saga and one night, someone even followed me all the way to my home! Normally, I would have been very concerned and driven to a police station but I realised that they were curious about the car. When I got down, a couple approached me and asked if they could take a look, so I let them.

Biggest launch program for a new model

In the months that followed the launch of the Saga, EON embarked on a series of events that would be the biggest and most extensive in the history of the Malaysian auto industry. The first of its ‘Sagathon’ events saw more than 88 Sagas being driven from Kuantan to the top of Genting Highlands. The cars were driven by the owners themselves who would test the car’s capabilities on what had become a ‘public test course’ for motorists because of its steep climb.

The event was intended to counter rumours that the Saga was underpowered (one rival company even created a scene suggesting the Saga would struggle uphill) and would overheat when it encountered steep slopes. But all the Sagas got to the top – with a full load of passengers as well – without any strain and more importantly, no overheating.

Later on, when the Saga 1.5I with an automatic transmission was launched, the media was also given the opportunity to test its capability on the Genting road. On this occasion, the engine did overheat but it was not due to it not having enough power. There had been a mistake in the way the wiring was done for the electric radiator fan and when I switched off the air-conditioner (since the outside air was cool), the fan was disabled as well. So when the engine had to work harder and naturally got hotter, the fan didn’t come on as it should have when the temperature goes over a certain level. I didn’t consider it a flaw and it was rectified immediately by Proton.

EON went all out to get Malaysians to personally experience their National Car so as to dispel any perceptions of poor quality or inadequate performance. It had a SagaUji program which was run nationwide and cars were brought to residential areas to offer test-drives.

Interest in the car was so great that EON kept its showrooms open till midnight, starting with its biggest one along Jalan Ampang in Kuala Lumpur. As more and more cars were sold within a short time, the service centres also began extending their operating hours – which was something new then – and owners were able to send their cars for servicing after normal office hours.

The National Car project was not just about making cars but also boosting the entire car industry, which included retail activities as well. To this end, besides having its own network of outlets, EON also appointed 41 dealers around the country.

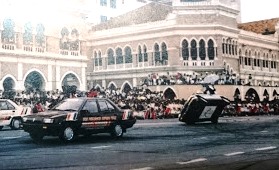

Saga taxis

The first Saga taxis appeared within about 6 months during the Sagathon Wilayah Persekutuan held in conjunction with Kuala Lumpur City Day. There were 112 of them and they gave free rides to city folk. It was not surprising that the Saga quickly became the choice of taxi operators as its reliability was proven in many ways and it was less costly to acquire. Had it not been for the economic slowdown at that time and a freeze on taxi permits, sales of the Saga to the taxi segment would have been much higher.

Giving more attention to customers was becoming important as companies wanted to enhance the ownership experience of car-buyers. This led EON to start Talian Saga, a ‘hotline’ service specially to answer enquiries about the Saga and provide assistance to owners, as well as obtain feedback on the product and services. EON’s General Manager, the late Datuk Gurcharan Singh, got personally involved in Talian Saga and reviewed every enquiry before passing it on to the relevant department for action or response within 24 to 48 hours.

Also new in the industry at that time was a loyalty card program. Called the EON card, it gave Saga owners exclusive benefits such as discounts on parts and services as well as special offers on other items including insurance. Cardholders received Sinaran Saga, EON’s newsletter, regularly and later on, a magazine as well.

Every opportunity to showcase the Saga was exploited, and cars were provided for many international events held in Malaysia. These included the World Journalist Convention, World Endurance Championship (yes, a round was held at the Batu Tiga circuit), Merdeka Tournament and Malaysian Open Athletics Championship.

The Sabah-Sarawak Sagathon

Looking back, I would say the most significant event related to the introduction of the Saga was the Sabah-Sarawak Sagathon. For some reason which I can’t remember, I did not take part in it but many of my media friends did and they came home very impressed by how the Saga performed. 12 standard cars were driven 1,111 kms over rough roads and tracks, a true endurance test.

Even the air force supported the event by providing a C-130 Hercules to transport the participants and the Saga of the Raja Muda of Selangor from Subang to Kota Kinabalu, the starting point. And to get from Sabah over to Sarawak, the air force again provided transport to fly over Brunei (although the cars went by ferry).

Strong start in the market

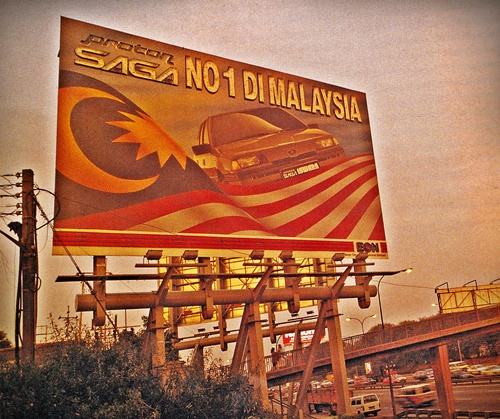

EON did just about everything to give the Saga a strong start in the market. In the first year, sales only started during the second half of the year and around 7,500 cars were delivered. The Total Industry Volume that year was about 68,000 units and Proton already captured an 11% share. The next year, its sales rose to 24,100 units and it accounted for 47% of the market. 1987 saw Proton – with just the Saga – selling more cars than the rest of the other brands combined and taking a share of 65%.

Eager to get onto the global arena, Proton began exporting the Saga just a year after its launch, with Bangladesh being the first country to get the Saga. In time, Malaysian cars would be sold in over 50 countries with Singapore, the UK, Germany and Australia being the biggest markets.

The original Saga was produced for 23 years – perhaps much longer than intended. Though it gradually became somewhat outdated, it was well established and remained affordable so sales didn’t slow down till the 2000s. It fulfilled its original mission of providing affordable personal transport and by continuing to buy the Saga, Malaysians also helped the auto industry to grow because the supporting industries also gained increasing business.

Click here for other news and articles about Proton.