Nobody can see it, but it is a factor in a car’s fuel consumption, safety and comfort. It’s called aerodynamics, or the study of how air moves around solid objects. In the automotive world, its application is very practical: reducing a car’s resistance to wind. And all this is tested in its ‘temple’, the wind tunnel. This is how it works.

A hurricane in the room

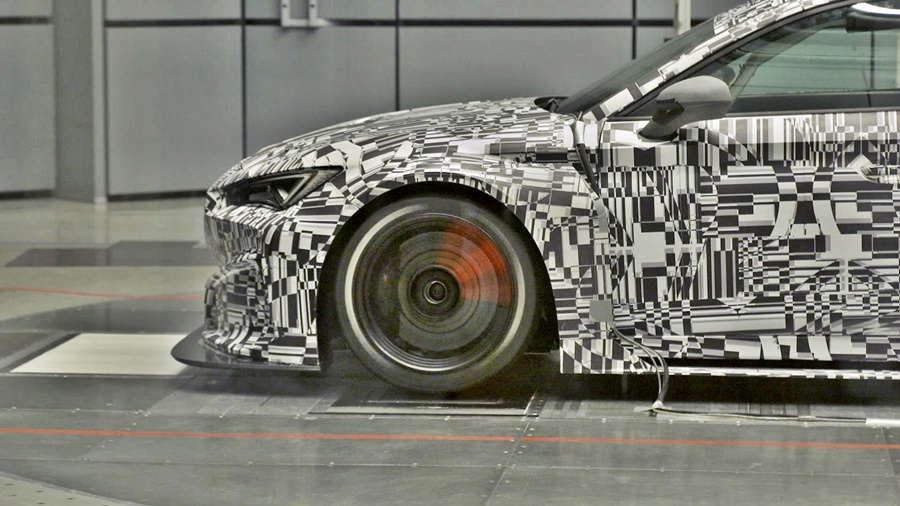

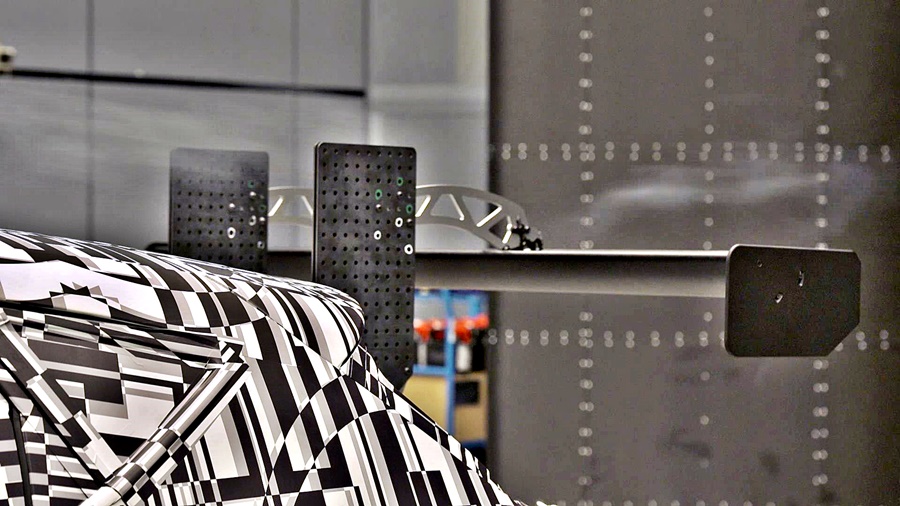

Typically, prototypes are placed in the middle of a chamber, securely kept to the floor. Huge fans generate airflow and the vehicles can face winds of up to 300 km/h while sensors study their individual surfaces.

The air travels in a circular motion, depending on the size of the rotor and blades. Needless to say, when it’s blowing at full power, no one will be allowed inside the chamber as they would literally get blown out of it.

The car’s resistance data is displayed on the computer screens. Hundreds of numbers to be interpreted and compared to even the smallest variable to improve aerodynamics. Every millimetre of each part is key, since it is not only possible to reduce consumption, but also to increase stability, comfort and safety.

Shaping to go faster

Wind tunnels, while primarily used for development of future models, are also valuable for racing cars. While the goal in aerodynamic efficiency for production models is to lower fuel consumption and improve stability, when it comes to racing cars, optimising the bodywork to achieve higher speeds is the aim.

CUPRA Racing’s Head of Technical Development, Xavi Serra, explains: “We want the new CUPRA Leon Competicion to have less air resistance and more grip when cornering. First, they will have to compete against the wind. Here we measure the parts on a 1:1 scale with the real aerodynamic loads and we can simulate the real contact with the road. This gives us the result of how the car will perform on the track.”

235 km/h standing still

The facilities where the CUPRA engineers test their prototypes are among the most complete and innovative. They have a special feature that makes the tests seem as if they are made in near-real conditions. However, instead of the car travelling at up to 235 km/h, the same effects are achieved by making the air travel at those speeds.

“The most important thing is that we can simulate the road. The wheels turn thanks to electric motors that move belts under the car,” said Wind Tunnel engineer Stefan Auri.

After hundreds of measurements, the results are compared with the car’s previous generation. “In this sense we’re satisfied; we’ve lowered the drag and improved the downforce, so it’s more efficient than the previous model, which will give us better lap times on the track,” said Xavi, adding that the data obtained will also be used to improve the new CUPRA models.

Supercomputer crunches numbers

The wind tunnel is not the only tool for improving aerodynamics. Supercomputing also plays a key role. When a model is in the early stages of development and there is not yet a prototype to study in a wind tunnel, 40,000 laptops working in unison are put to the service of aerodynamics. This is the MareNostrum 4 supercomputer, the most powerful in Spain and the seventh in Europe. Scientists around the world use it to carry out all kinds of simulations, and in the case of a collaboration project with SEAT, its computing power is used to battle the wind.

Watch: Onboard a race-spec Seat Cupra around Sepang Circuit!