Yamaha is a well known name in the motorcycle world, especially in motorsports. And while most people know the Japanese manufacturer for its motorcycles, it actually has a history of making high-performance engines for other manufacturers. In fact, as far back as 1959, Yamaha engineers carried out basic research in automobile engine development and produced a 1.6-litre DOHC unit of exceptional power output.

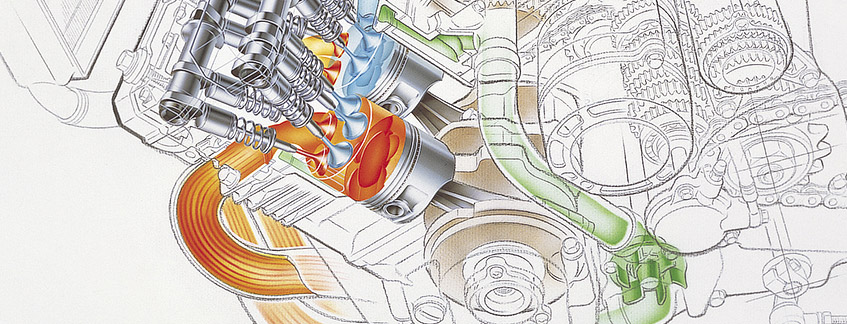

It collaborated closely with Toyota on the 2000 GT supercar as well as the development of Toyota’s engines such as the 2T-G, 3S-GTE, 1Z-GTE and many others. One of the notable features of its engines was multivalve technology which Yamaha engineers contended offered the highest potential. This is because of the increased effective intake valve surface area, the possibility of a higher compression ratio due to more compact combustion chambers, and lighter valve mass.

In the late 1980s, Yamaha was also involved in Formula 1, after having established a strong track record in Formula 2 and F3000. In 1988, it teamed up with Zakspeed Formula Racing, to form a Formula One racing team known as the West Zakspeed Yamaha Team. The team entered F1 events with a new car using a Yamaha-developed engine, the OX88. The engine was a 5-valve DOHC V8 that had a displacement of 3489 cc and produced over 600 bhp.

Aguri Suzuki, who had already made the step up to Formula 1, joined the team and faced high expectations as the second ever Japanese Formula One driver following Satoru Nakajima. The team had a somewhat difficult time at first but in 1990, a compact, lightweight engine to succeed the OX88 was announced: the OX99. It was a 5-valve V-12 with a 3498 cc displacement, and its output was also over 600 bhp.

The OX99 proved to be a more competitive engine and Yamaha provided it to the Brabham, Jordan, Arrows and Tyrrell teams until 1997 when the company stopped its involvement in F1. The best result during the 8 years of taking part in F1 was a second place by Damon Hill, driving for the Arrows, at the 1997 Hungarian GP.

F1 car for road use

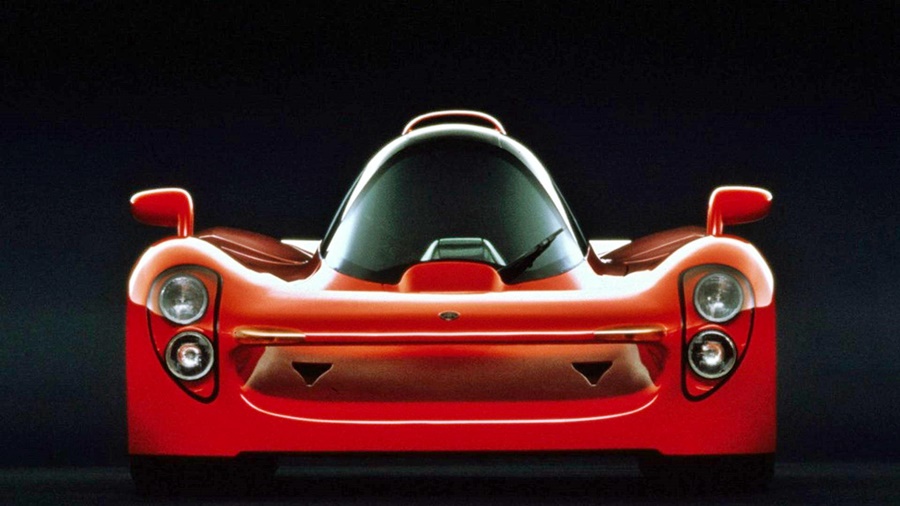

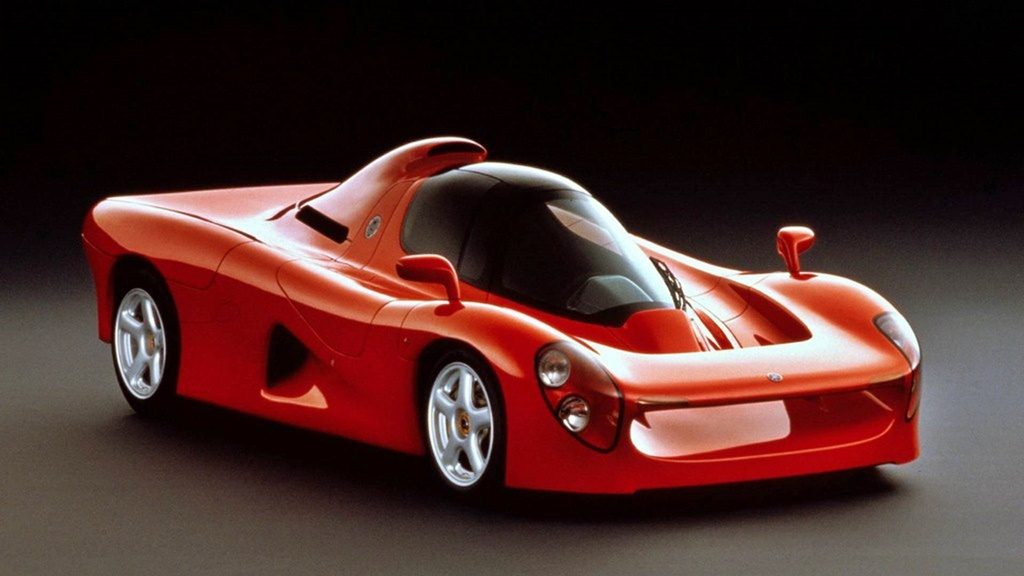

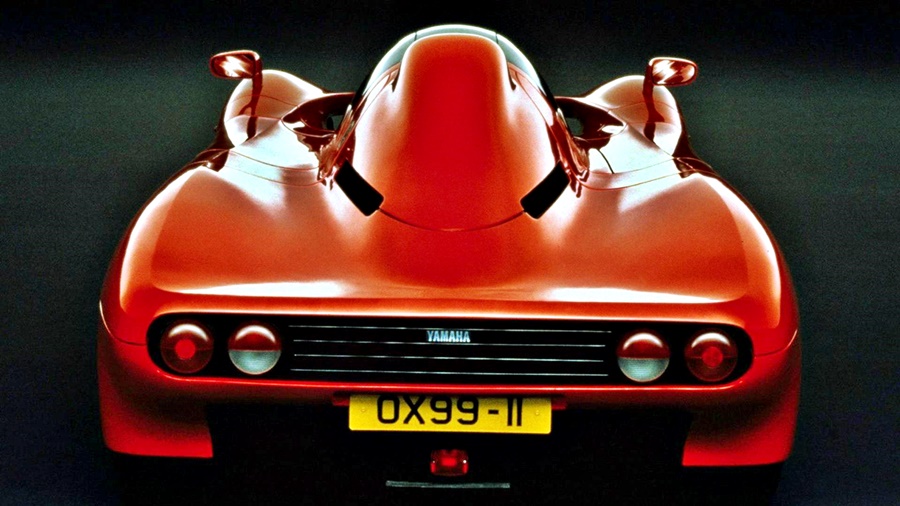

Using its experience in F1, Yamaha then started to develop a F1 car for the road which, in concept form, was known as the OX99-11. It had a seating position like a racing car – including a central steering position – but was configured to comply with legal requirements for road use. This meant having wheels enclosed within a wheel well, proper lighting units, reasonable ground clearance, and of course, low noise and emissions. The result was a car that looked like a scaled-down Group C racer.

Just as Honda (coincidentally another top motorcycle maker) made a strong technological statement with its NS-X, so too did Yamaha using the OX99-11 to demonstrate the company’s advanced capabilities in the field of automotive engineering. Yamaha planned to make up to 100 units for sale, with a launch date set in 1994.

At that time, T. Hasegawa, who was a senior Managing Director of Yamaha in 1992 and the man behind the company’s collaboration with Toyota for the 2000 GT said: “This project is part of Yamaha’s ongoing efforts to use its experience and technology to make exciting and meaningful contributions to the great tradition of motor culture. It represents our attempt to build the ultimate sportscar.”

The idea to make the car had started sometime in 1982 and a prototype was built using a 4-cylinder 2-litre engine for the Japanese F2 series. In order to make it practical for road use, the mid-mounted engine was detuned by changing the cam profiles, putting in a new engine management programme, and using a slightly heavier flywheel. However, the 10-litre dry sump lubrication system was retained to avoid fuel surge problems and it also lowered centre of gravity. Intake air was drawn through a port on the roof.

But in spite of being detuned, the 3.5-litre engine could still deliver 400 bhp and spin up to 10,000 rpm. Yamaha claimed that it had superior driveability and plenty of usable power from 1,200 rpm, fully exploited by the 6-speed transmission.

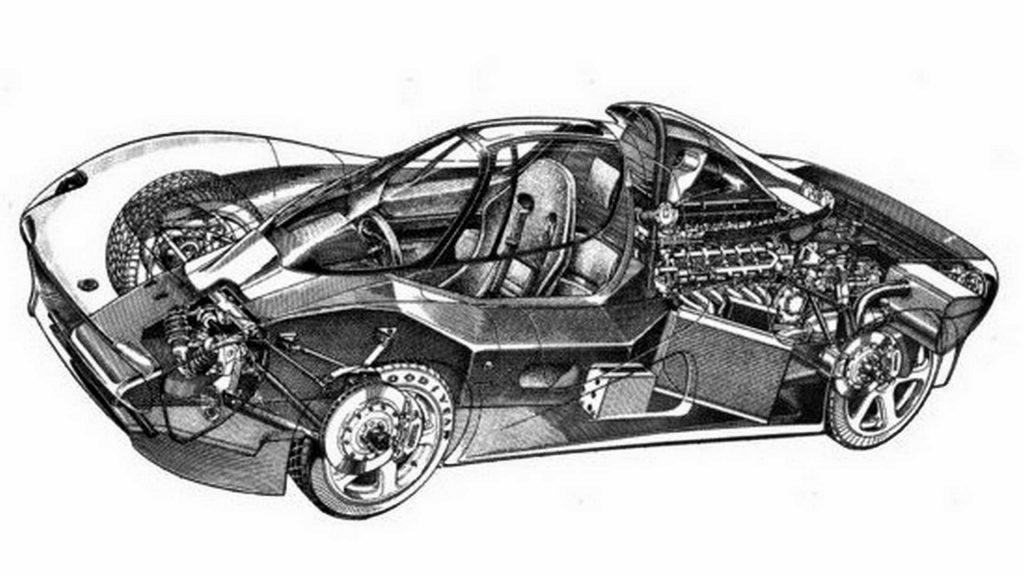

Underneath the aluminium bodyshell, the structure was the same as a F1 car with the engine and transmission bolted to the rear wall of the monocoque made of carbonfibre reinforced plastic (CFRP) and sandwiched aluminium honeycomb material. A roll-cage of CFRP was also installed around and over the cabin for extra protection. The driver sat in a safety tub with a small ‘passenger space’ behind, offset to the left. Entry was by raising the glass canopy hinged on the right side.

In the cockpit

Jet pilots would have felt right at home in the OX99-11 with the way the canopy wrapping around the cockpit. The shift lever was placed on the right panel adjacent to the starter button. But back then, electrical systems were simpler and though there was the button to start the engine, a key had still to be inserted to connect the electrical circuit! Because of the compactness, the steering wheel had to be removed to get out of the car.

Although the cockpit was longer than a F1 car, its width was limited because a large portion of the 120 litres of fuel carried was stored in the box sections on either side of the driver. This further enhanced weight distribution as the main mass was kept in the middle area of the car.

F1 suspension

Much of the suspension design and materials came straight off the F1 shelf; at the front and rear were double wishbones with inboard spring/adjustable damper units operated by pushrods. The suspension arms were long and thin with an aerofoil cross-section. Ground clearance could be varied using the body height mechanism.

The tyres for the OX99-11 were from Goodyear which worked with Yamaha on the project. Specially developed unidirectional Eagle 17-inch Z-rated tyres with an asymmetric pattern were installed, the front ones having a 245/40 and the back ones 315/35. The wheels were made of magnesium alloy and were 9 inches wide in front, 12 inches at the rear.

Super downforce

As to be expected, aerodynamic efficiency was top priority and the designers applied the ‘upside-down aerofoil’ idea exploited by Colin Chapman in his Lotus F1 cars. Thus, the OX99-11 was essentially profiled like an inverted wing, the entire shape generating downforce instead of lift.

The claimed overall coefficient of lift of -63 was believed to be the lowest ever attained for any road-legal car. While not as good as a full-fledged racing car, it was still impressive considering the height of the car which allowed air to ‘leak’ under it.

Each OX99-11 was to be hand-built at Ypsilon Technology, a Yamaha subsidiary established in England in 1990 which was responsible for maintaining and supplying Yamaha racing engines. Unfortunately, Japan’s ‘economic bubble’ burst in the early 1990s and Yamaha did not think that anyone would be interested in a supercar (which might cost as much as US$800,000). In the end, only three prototypes were built before the project was terminated.

DIMENSIONS

Length: 4400 mm

Width: 2000 mm

Height: 1220 mm

Wheelbase: 2650 mm

Tracks: 1615 mm (F) | 1633 mm (R)

Min. ground clearance: 100 mm