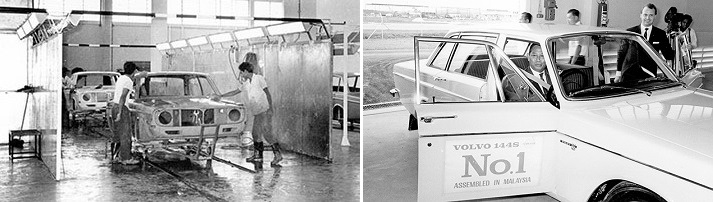

Government policies for the automotive industry are not new and go back to the mid-1960s when the first one started off the domestic auto industry as part of the young country’s shift towards industrialization. Recognised as one of the industries that had been a catalyst for economic and industrial and economic growth in America, Japan and Germany, the early policies created a framework for the industry and the business which would continue to this day, promoting local production.

The first policies were aimed at encouraging foreign carmakers – there were no Malaysian ones then – to assemble locally and incentives were offered. Besides preferential import duties that would enable locally-assembled models (completely knocked-down or CKD in the industry language) to be sold at lower prices than those imported completely built-up (CBU) from factories in other countries, there was also a push to promote the development of ancillary industries such as the components industry.

This saw the imposition of Mandatory Deletion for a certain number of items (around 20) such as paint, tyres, batteries, wire harnesses, windscreen glass, etc for which foreign companies had set up factories in Malaysia. To encourage this, a penalty tax of up to 3% (rising in 2% increments each year) was imposed on companies that did not include at least 8% of content made in Malaysia as at February 1968.

The basic policies for the auto industry were maintained until the 1990s when globalization made protectionist policies less acceptable. As a signatory (and founding member) of the World Trade Organization (WTO), Malaysia had to meet certain obligations with regards to fair trading practices although a grace period was given.

Among these agreements was the Trade Related Investment Measures (TRIMS) pact signed in 1994 which forbids measures by a government that require particular levels of local procurement (use of locally-made parts or local content) by any company or which restrict the volume or value of imports a business can purchase or use to an amount related (an example being the requirement to have an import permit which is not issued freely to all bonafide applicants).

Then there was also the ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA) which was formed. This was an attempt to create a big single market like the earlier European Economic Community (EEC) so that there would be greater attraction to investors as there was the potential of 500 million consumers.

Privileges such as duty-free exchange of goods and services between ASEAN countries were offered so that companies could set up production hubs and export around the region, achieving better economies of scale to lower production costs.

These developments impacted the somewhat insular Malaysian auto industry which had enjoyed protection in various ways since 1967. By 2002, the local content requirement was abolished and likewise the control of pricing (of CKD models) by the government also ended and market forces determined prices. Nevertheless, some protectionist elements were still retained although the NAPs have tried to moderate them.

The National Automotive Policy (NAP) provides a ‘road-map’ for participants in the Malaysian auto industry to do forward-planning, taking into consideration the fact that such planning often covers a time-frame of 5 to 10 years. It indicates the direction to be taken and the incentives available which matter a lot to those who consider investments running into the hundreds of millions.

The original NAP was not warmly welcomed as it was seen to be protectionist. Its failure to attract foreign carmakers (or even raise their investments) was acknowledged by the MITI minister then. While protecting domestic industry is in the ‘national interest’, there needs to be a balance if Malaysia wants to be the regional automotive hub it has long aspired to be.

Like the 2-year delay for the announcement of the previous NAP in 2014, the 2020 NAP was also delayed some time. Officially, MITI minister Datuk Ignatius Darell Leiking said that it had not been ‘delayed’ but was being ‘fine-tuned’. Anyway, the latest NAP has finally been launched today by the Prime Minister and it is the fourth one to be formulated since 2006.

NAP Number 4

The new NAP has been formulated with a more global view and a National Automotive Vision to guide the country to become a regional leader in manufacturing, engineering, technology and sustainable development. The overall expectation of what this forward-looking NAP can achieve is more R&D for new technologies, creation of business and job opportunities, and the development of new manufacturing processes and value chains within the local automotive and overall mobility sector.

Actually, the new NAP can be considered an enhancement of the previous one, facilitating the required revolution and optimal integration of the local automotive industry into regional and global industry networks.

The new policy is expected to be used until 2030 and in its framework, there are three directional thrusts which will focus on development of the Next Generation Vehicle (NxGV), Mobility as a Service (MaaS), and Industrial Revolution 4.0 (IR 4.0). There are also three strategies which are Value Chain Development, Human Capital Development, and Safety, Environment & Consumerism.

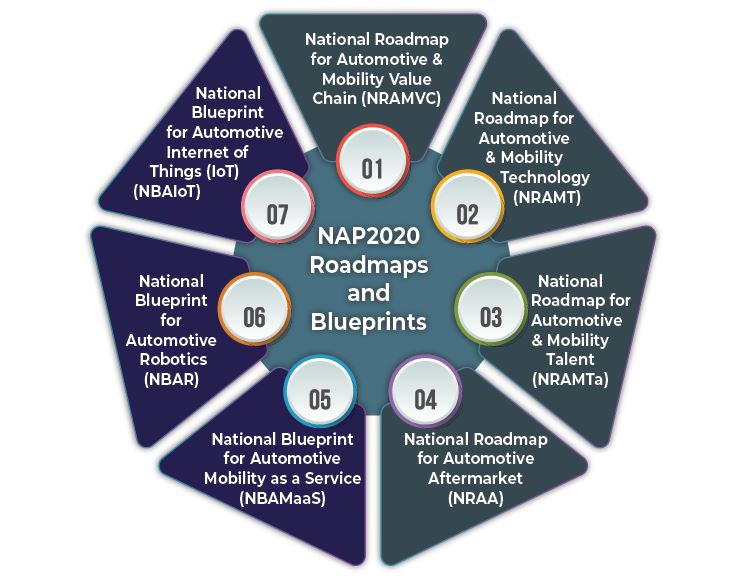

Just as old geographical maps used to be quite general in presentation and today’s digital maps can zoom right down to a house location, the NAP has no less than 4 detailed National Roadmaps that provide information and guidance, as well as another 3 National Blueprints that will serve as guiding principles and reference in implementing the measures and strategies of NAP 2020.

The objectives of the previous NAP continue and these include developing a competitive and capable domestic automotive industry as well as making Malaysia a regional automotive hub in Energy Efficient Vehicles (EEVs). There has always been a desire to increase exports of vehicles, but cost-competitiveness is challenging because the factories here do not have economies of scale to challenge the big ones in Thailand and Indonesia.

However, automotive components, spare parts and related products in the manufacturing and aftermarket sector have a better chance of being export-oriented and many Malaysian companies have already gained supply contracts overseas. Some of them even supply to companies in Japan, where high quality is expected.

EEV and NxGV

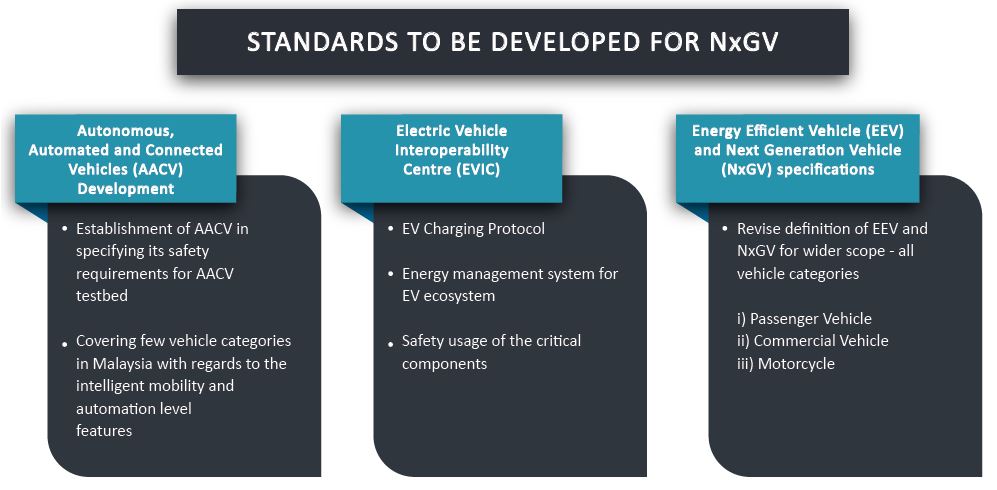

The EEV initiative began with the previous NAP and promoted the development of R&D capabilities for right-hand drive vehicles and related technologies, such as fuel efficiency, light materials, telematics, tooling and component design. NAP 2020 will continue this program with a review and revision of EEV standards, and will also include commercial vehicles and motorcycles above 250 cc.

NxGV is classified as a vehicle that meets the definition of future EEV classifications and is enhanced with Intelligent Mobility applications. NxGV vehicle technology has 5 levels and the minimum will be of Level 3 Vehicle Automation, ie Conditional Automation. So rather than being a new ‘vehicle type’, it appears to be essentially a more advanced EEV (which many of today’s models already qualify as).

By next year, standards for the NxGV will be announced to ensure safety requirements and protocols for high precision systems and processes, particularly electric vehicles (EVs). The aim is to have NxGV standards for all vehicles by 2025 so commercialization can proceed.

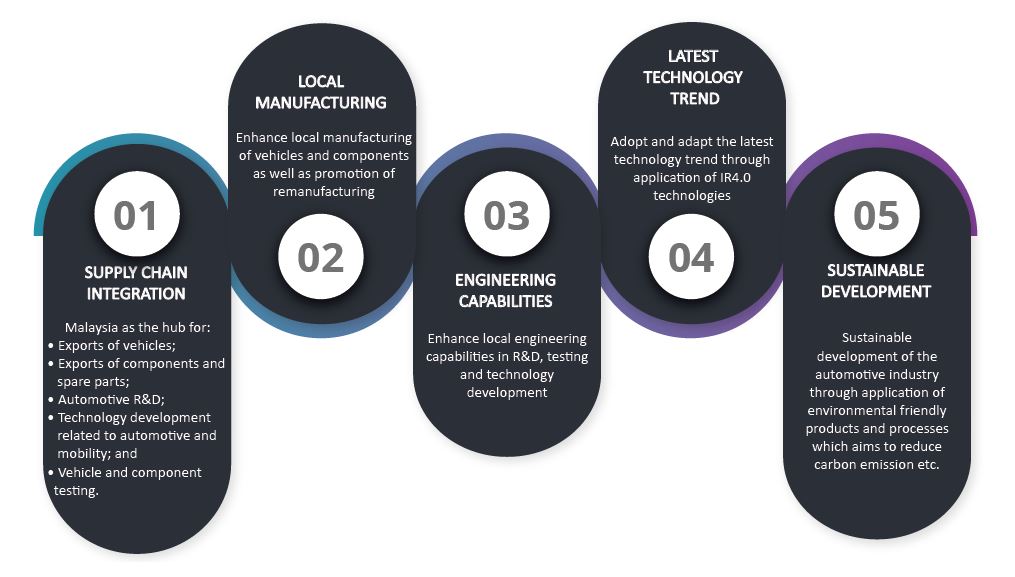

The National Automotive Vision

Unlike previous NAPs, the new one includes a National Automotive Vision which explains what the government wants to achieve so that efforts can be focused appropriately. The main aim is to make Malaysia a hub for exports of vehicles, exports of components and spare parts, automotive R&D, development of automotive and mobility-related technologies, and vehicle and component testing.

This vision, to be realized by NAP 2020, is aimed at promoting local manufacturing activities in vehicles and components which will reduce imports of vehicles and components as well as spare parts. At the same time, it also aims to implement the transformation of the automotive sector to enhance local engineering capabilities which in turn will create opportunities in the services sector for R&D, testing and technology development activities.

Mobility as a Service (MaaS)

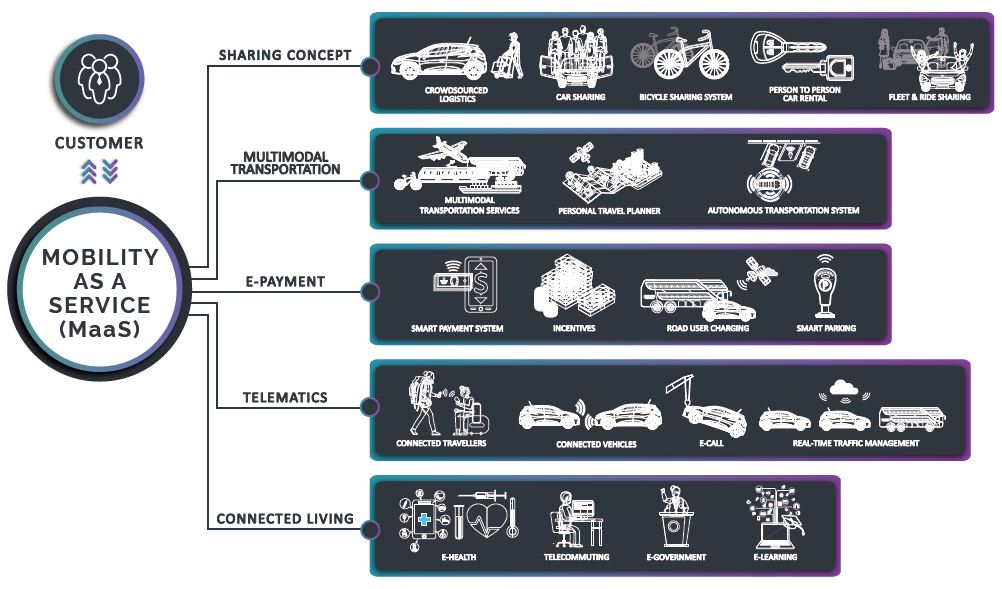

MaaS is a concept to integrate various types of services and transport modes into an efficient and centralized mobility service. It provides a wide range of transportation options such as a combination of public transport services and private vehicles, besides enabling users to enjoy other services such as optimized product delivery services, online health diagnostics and others.

The Multimodal Transport system will be complemented by e-payment, telematics and connected living. As innovative new mobility services become available, MaaS will evolve to adopt them, ultimately benefiting the traveler and the environment, especially in urban areas. It will also create a new ecosystem that will strengthen and improve the automotive industry.

The technology thrust includes UAVs (like drones) and Air Mobility (the flying car?) which can be part of connected mobility in future. Specific measures call for coordination and development of regulations before mass utilization.

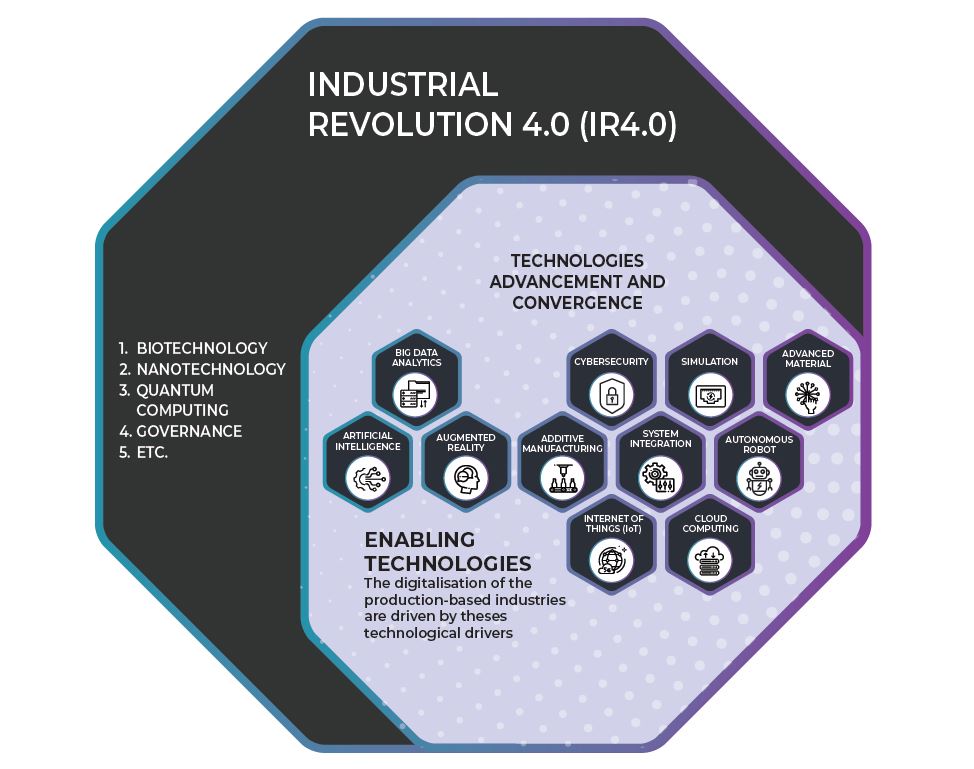

Industrial Revolution 4.0 (IR4.0)

IR4.0 refers to the application of digital technology beyond the technological elements under Industry4WRD. The use of IR4.0-related technology applications especially AI, Big Data Analytics and IoT (Internet of Things) will enable the implementation of NxGV and MaaS.

Digital technology came with the advent of the computer age in the 1970s and has become an integral element in the auto industry. IR 4.0 represents the digital transformation of the industry based on the adoption of new technologies for the progressive automation of the production process.

The key enabling technologies such as additive manufacturing, collaborative robotics, production planning tools, Artificial Intelligence, virtual reality, gamification, process simulation, operational intelligence, IoT, and Big Data Analytics requires a system that operates and manages information and infrastructures towards creating a connected mobility ecosystem.

The enabling technologies will soon drive the industry towards envisioning a connected and integrated environment, a system of vehicle-to-vehicle communications, cameras, variety of sensors (Radar, LIDAR, RFID, etc.) and other devices integrated with advanced algorithms that can monitor the road in a variety of road, weather and traffic conditions to enable autonomous systems.

Attracting investments, expanding the market

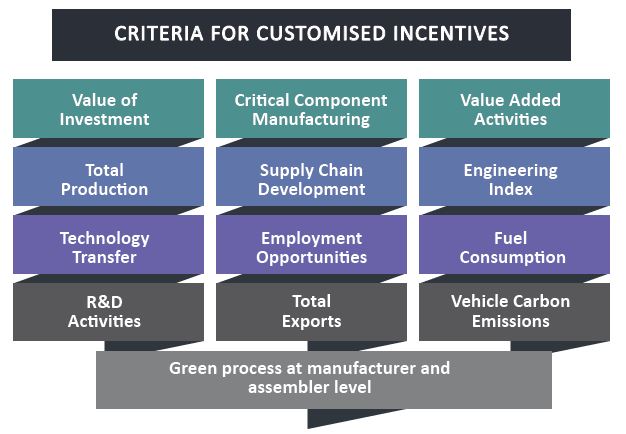

The NAP is intended to attract investments in order to meet its targets. As has been the case since the 1960s, there will be incentives which include more competitive investment opportunities, including a more comprehensive mechanism for Customized Incentives and assistance to facilitate business operations.

While ‘customized incentives’ sounds very investor-friendly, it also makes some companies uncomfortable when only criteria are made public. This was already apparent with the previous NAP where incentives were not totally transparent as interested investors were invited to have private meetings with the relevant agencies to discuss what they could offer and what could be given in return.

Global players especially (the ones which can make big investments) have felt this ‘back door’ approach does not make for fair negotiations as they do not know what another party may actually get. They point to countries like Thailand and Indonesia which make incentives clear, open and applicable to all parties who want to ‘play’. It could well be the reason Malaysia is not a high priority when it comes to considering investments in the auto industry and commonising incentives for all may be a better way.

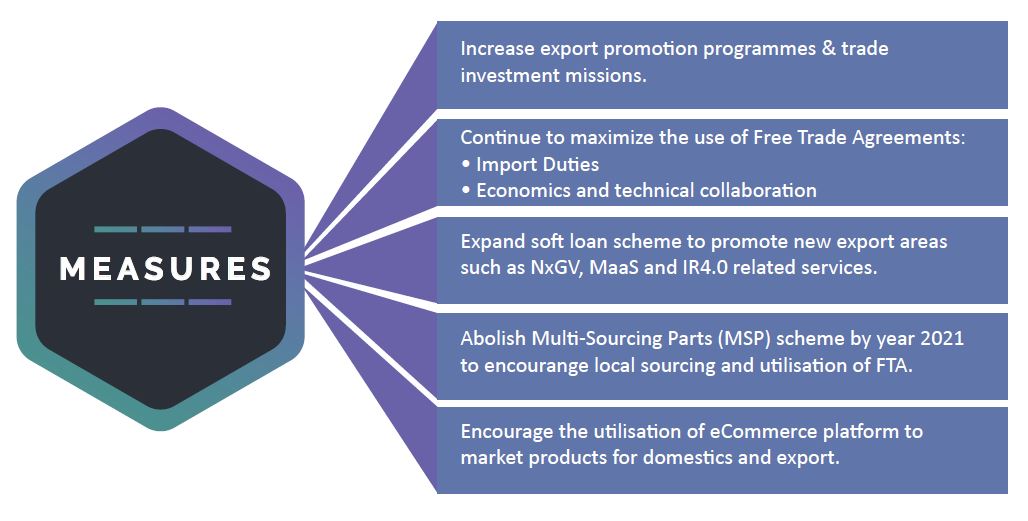

With its limited market size, Malaysian businesses will clearly have to look beyond our borders to continue growing. The introduction of the elements of technology and services in NAP 2020 will create both the MaaS and IR4.0 ecosystems that will provide opportunities to expand access to international markets.

Malaysia has signed a number of Free Trade Agreements with different countries to help in export programmes and these will be further utilized. NAP 2020 also encourages the expansion of soft loans to promote new export areas such as NxGV, MaaS and IR4.0 related services, besides encouraging the use of eCommerce platforms to market products domestically and overseas.

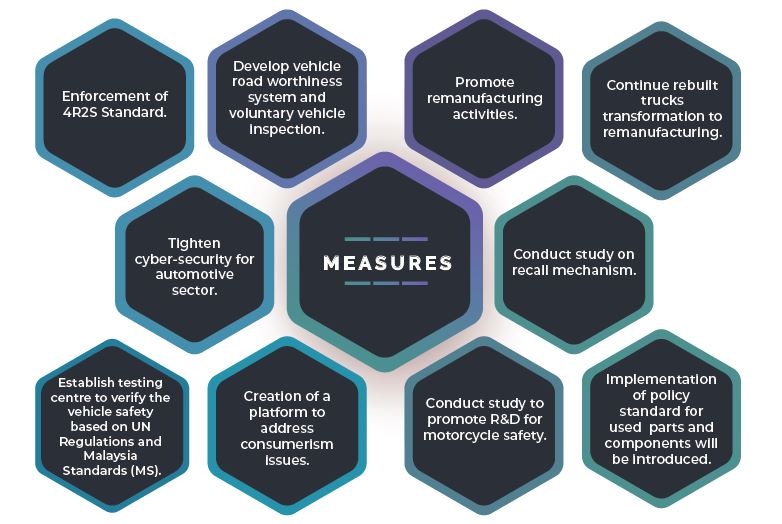

Attention to safety and the environment

With increased concerns about climate change and reducing accidents, NAP 2020 also makes sure that there is attention given to new, more environmentally-friendly elements of technologies that will address the issue of pollution. One objective is to reduce carbon dioxide emissions from vehicles by improving the fuel economy level in Malaysia to 5.3 Lge/100 kms (Lge refers to Litres of gasoline equivalent) by 2025 in line with the ASEAN Fuel Economy Roadmap of for the transport sector.

Besides the move to B20 diesel yesterday and the planned move to B30 by 2025, the NAP also mentions that petrol specifications will go from the current Euro4M for both RON95 and RON97 to Euro5 by September 2025. That’s the sort of information which the industry welcomes as planning can be done to use more advanced and environment-friendly engines that require fuel of higher quality.

Focussing on the safety of vehicles and consumers will include consumerism elements to protect consumer rights related to spare parts and services. Long-overdue matters such as compulsory inspections for all types of vehicles will also be considered and there will be more R&D on motorcycle safety. Eventually, there is to be a proper testing facility to carry out inspections on vehicles that are submitted for Type Approval.

Bumiputera participation and APs

Recognising that the auto business had limited Bumiputera participation, the government introduced the Approved Permit (AP) system in 1970 to help Bumiputera businessmen enter the sector. The idea was for them to be able to import motor vehicles and start businesses which could grow and increase their presence in the industry.

NAP 2020 will continue with the support to Bumiputeras wanting to get into the automotive sector through participation in the supply chain and other new business activities. The controversial system, supposed to end on a few occasions, will also continue to provide opportunities to qualified Bumiputera automotive entrepreneurs to be involved in importation of used cars and motorcycles.

The fee for one AP is maintained at RM10,000 for one unit of car approved under the Open AP system. This rate is applicable for the first 35,000 units for all Open AP companies under the validity period of AP provision of the current year. The fee for the subsequent approved AP unit is RM20,000 for each vehicle unit imported by Open AP companies.

The New Open AP Policy also requires that the company granted with the AP must provide buyers with at least a 1-year warranty and maintenance service or in cooperation with the manufacturer for the maintenance service.

The Franchise AP Policy is also continued for the purpose of monitoring and data collection. This policy will be implemented in line with the improvements proposed for the automotive industry as a whole, by promoting and opening greater opportunities for participation of Bumiputeras in the automotive supply chain and not only focusing on being an importer.

New Malaysian Vehicle Project

Since last year, there has been talk of a third national car project and this project is incorporated in the NAP 2020. As it is of great interest to the public, we will provide insights in a separate article. The purpose of the new Malaysian Vehicle Project, which will develop 2 cars and 1 motorcycle, is in line with the future direction and strategies of the Malaysian automotive industry and helps to fulfil the National Automotive Vision. [Click here to read more about the New Malaysian Vehicle Project]

Targets by 2030

So what is expected to be achieved by 2030? NAP 2020 has many targets to aim for (as shown in the charts below). Some targets are compared to NAP 2014 but with different values; for instance, the target for exports by 2020 was 250,000 units (which is not reached) but by 2030, the target is set at RM12.3 billion. This is, of course, based on current values and who knows how things will change by the end of the decade.

Then there’s the Total Industry Volume (TIV) which refers to sales of new vehicles in the country – 1.22 million units by 2030. NAP 2014 had set a target of 1 million units in one year by 2020 but that was a rather ambitious number. Last year, the TIV was just over 600,000 units and the Malaysian Automotive Association, in consultation with the car manufacturers, has forecast growth of only 1% or 2% a year for the next 5 years.

The same over-optimism seems to be in production volumes although this could well get boosted if exports do grow rapidly or manufacturers begin to include Malaysia in their future investment/expansion plans as a means of having additional backup locations in the event of disruptions caused by floods, earthquakes or epidemics (as we are now witnessing). NAP 2014 had set an annual production volume of 1.35 million units by 2020 but last year, the total volume from 22 plants was around 570,000 units.

Exports of components has much potential and where NAP 2014 set a target of RM10 billion, the aim is to reach RM28.3 billion in export value by 2030. This is an area where Malaysia could work towards becoming a regional hub since it is harder to be a hub for vehicles when the big factories in neighbouring countries already have high volumes. And with the emphasis on developing technologies that are more advanced in many fields, there could be an inclination for global suppliers to set up bases here. Of course, it still depends on incentives offered which must be attractive enough against other countries.

Also, the stability of policies must be assured and this seems to be promised with the ‘lifespan’ of this NAP set to cover the period up till 2020. A sufficiently long period gives investors more comfort in forward planning. But what some companies fear is while the policies may be maintained for 10 years, incentives might change since they are not openly stated and therefore can be varied at anytime for anyone.

The New Malaysian Vehicle Project (aka as Third National Car Project)