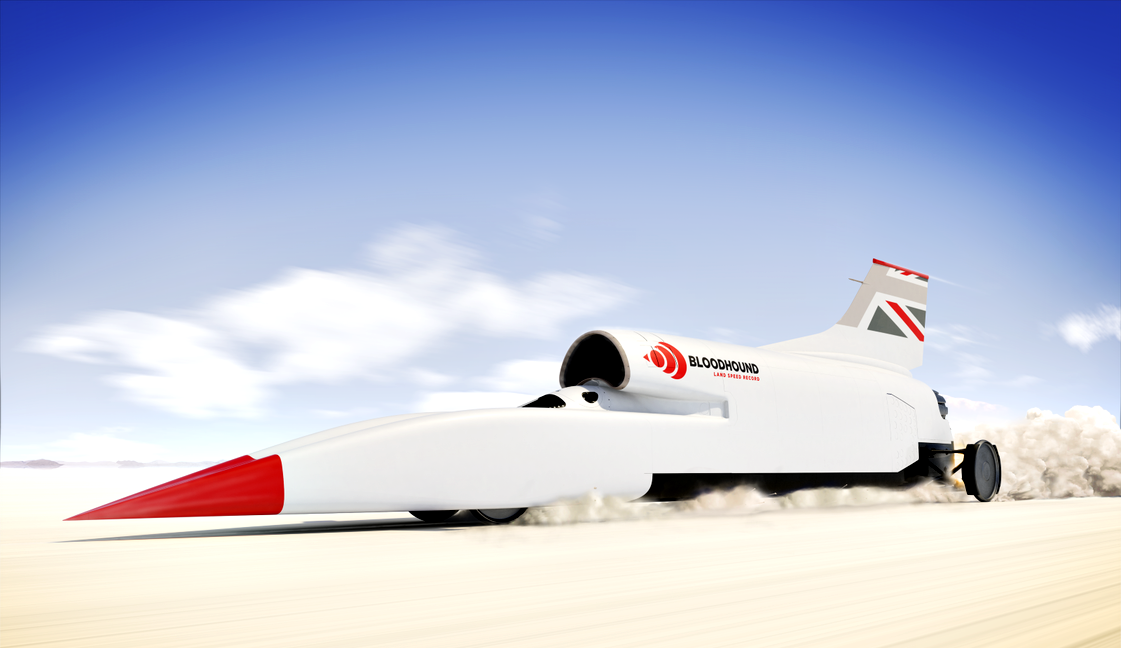

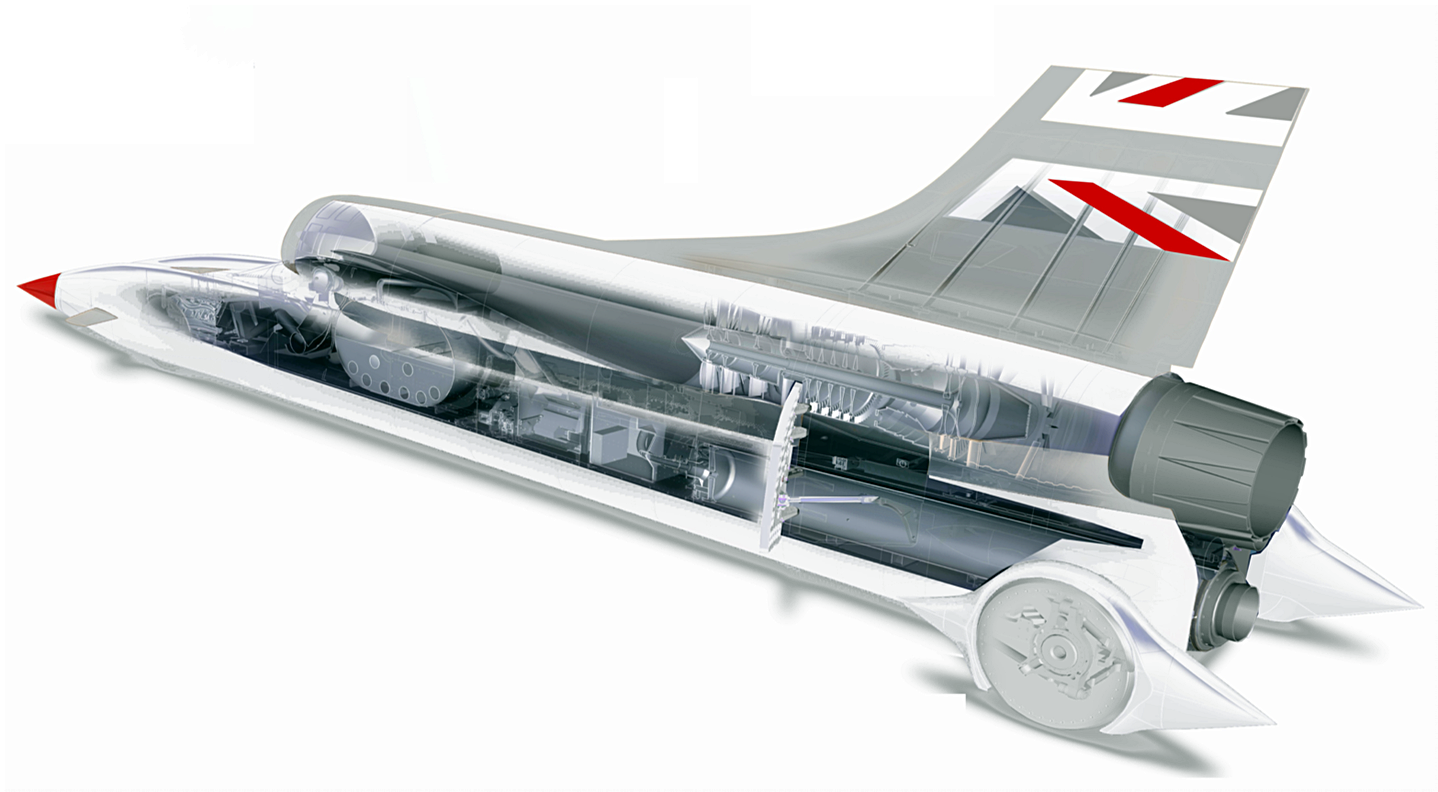

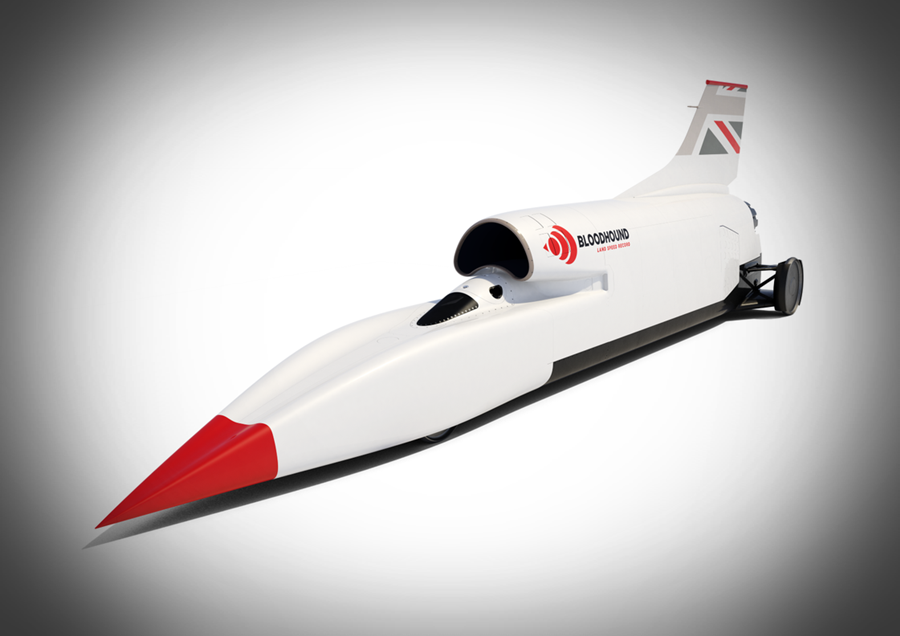

To be the most powerful straight-line car on the planet, the Bloodhound LSR is fitted with a Rolls-Royce engine but it’s not an engine you get in the Rolls-Royce Phantom. It’s the EJ200 jet engine made by the other Rolls‑Royce company and which is normally found on the Eurofighter Typhoon fighter jet.

The output for this jet engine is a monstrous 9 tonnes of thrust (90 kN), equivalent to approximately 54,000 thrust horsepower – about the same as the combined output of 360 medium-sized cars. That will rocket the Bloodhound to a mind-blowing speed of 800+ km/h which is as fast as a commercial airliner’s cruising speed. On solid ground, that would definitely place it amongst the 10 fastest cars of all time.

At full design speed, the Bloodhound LSR could cover 1.6 kms in 3.6 seconds – or 150 metres in the blink of an eye. The World Land Speed Record of 1,227.9 km/h is held by the Thrust SSC which was set in 1997 by a UK team led by Richard Noble and driven by Andy Green.

The project is now split into two phases. Phase one’s target is to break the existing World Land Speed Record. This is necessary to understand how the car behaves as it enters the transonic stage initially and then supersonic speed levels. Upon the successful completion of the first phase, the team will review the data and technical challenges before embarking on phase two, and the challenge of safely reaching 1,600 km/h.

A 9,000-km journey to set a new record

The project has reached the final phase of its build programme as it prepares to head to South Africa and be put through its paces in a series of high-speed shakedowns on the vast Hakskeenpan desert in the Northern Cape.

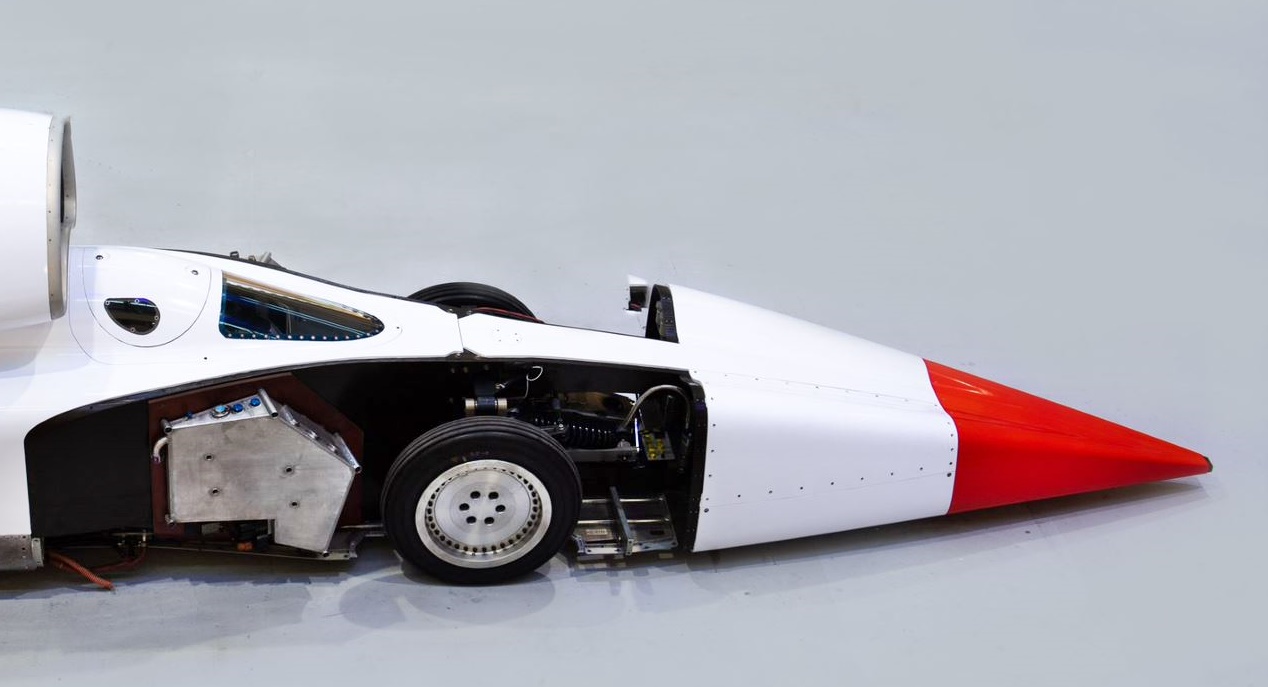

Moving the 6.4 tonne Bloodhound LSR 9,000 kms from the UK to South Africa throws up major logistical challenges in itself. Much of the heavy support equipment, including the car’s trailer, has already set off to make the long journey by sea but the car itself will travel via air freight to ensure it isn’t subjected to any uncontrolled shock loads that could damage it in transit.

The EJ200 jet engine will travel mounted inside the upper chassis, which is where you would find it in its natural home inside the Eurofighter Typhoon. The 2-metre-high tail fin, which is the same size as that found on a Red Arrows display jet, has been removed and will travel upright in a wooden crate, along with some sections of the composite bodywork.

The car will be fitted with the wheels shod with pneumatic tyres that were used for UK runway testing at Cornwall Airport in October 2017, where they carried the car at speeds of up to 320 km/h. For testing in South Africa, the wheels will be changed from pneumatic to solid aluminium discs to cope with the high speeds and desert environment.

The 90-kg desert wheels are produced by a consortium of partners including Castle Precision Engineering, who recently balanced the wheels to ensure they conform to Class G2.5, the same as aircraft turbine blades. This involves an exacting process of shaving microns of aluminium from the spinning discs to ensure they’re perfectly balanced and ready for the desert.

Crucial testing stage

This stage of the testing process is crucial, as the 480 – 900 km/h window is one of the most vulnerable stages for the car. It’s at this point that the stability of the car transitions from being governed by the interaction of the wheels with the desert surface to being controlled by the vehicle’s aerodynamics. The grip from the wheels will fade faster than the aerodynamic forces build up, so this is likely to be the point where the car is at its least stable.

Data on the interaction between the solid aluminium wheels, which are being used for the first time, coupled with ‘base drag’ measurements, will provide real world insight into the power required to set records. Base drag relates to the aerodynamic force produced by low pressure at the rear of the car, sucking it back. As the car approaches transonic speeds, this force far exceeds the friction of the air passing over Bloodhound’s bodywork.

“Transforming Bloodhound from a runway spec car to one capable of reaching speeds in the transonic range on the desert racetrack has been no small task,” said Bloodhound LSR Engineering Director Mark Chapman. “After many years in preparation, we can’t wait to get out to the Hakskeenpan and let Bloodhound off the leash to see just how it performs.”